WOAD

Woad is a twelve-page hand-tufted story, my senior thesis body of work at MassArt. Influenced by my Omi and her experience with dementia, the story follows woad-dyer Elisabet and her Ancestor. As a physical body of work, Woad consists of twelve 30” x 38” machine tufted panels made during the spring of 2021. The panels were then photographed and oriented into an easily-distributable digital and print format, as a way to further share my artwork during the Covid-19 pandemic. You may read Woad and a longer statement below ! (print copies are available, email me )

Woad (Isatis tinctoria) is a plant native to the Mediterranean, commonly used for dyeing in Medieval Europe and Britain. The woad plant is a biennial- growing a group of spinach-like leaves in its first year. This is where the dye comes from. In its second year, the plant may grow up to 6 feet tall and blossoms with bright yellow flowers in early May, around when Mathilde’s birthday fell.

Woad leaves are harvested in summertime and crushed into a loose pulp. The pulp is fermented in small heaps and allowed to dry, having a shelf life of up to a few years.

The woad dye vat is very similar to indigo. The addition of an alkaline solution helps the woad to fasten to the fibre. The dye becomes a dark yellowy green with a shimmery blue flower on top. The more times one dips and oxidizes the fibers, the darker blue they become.

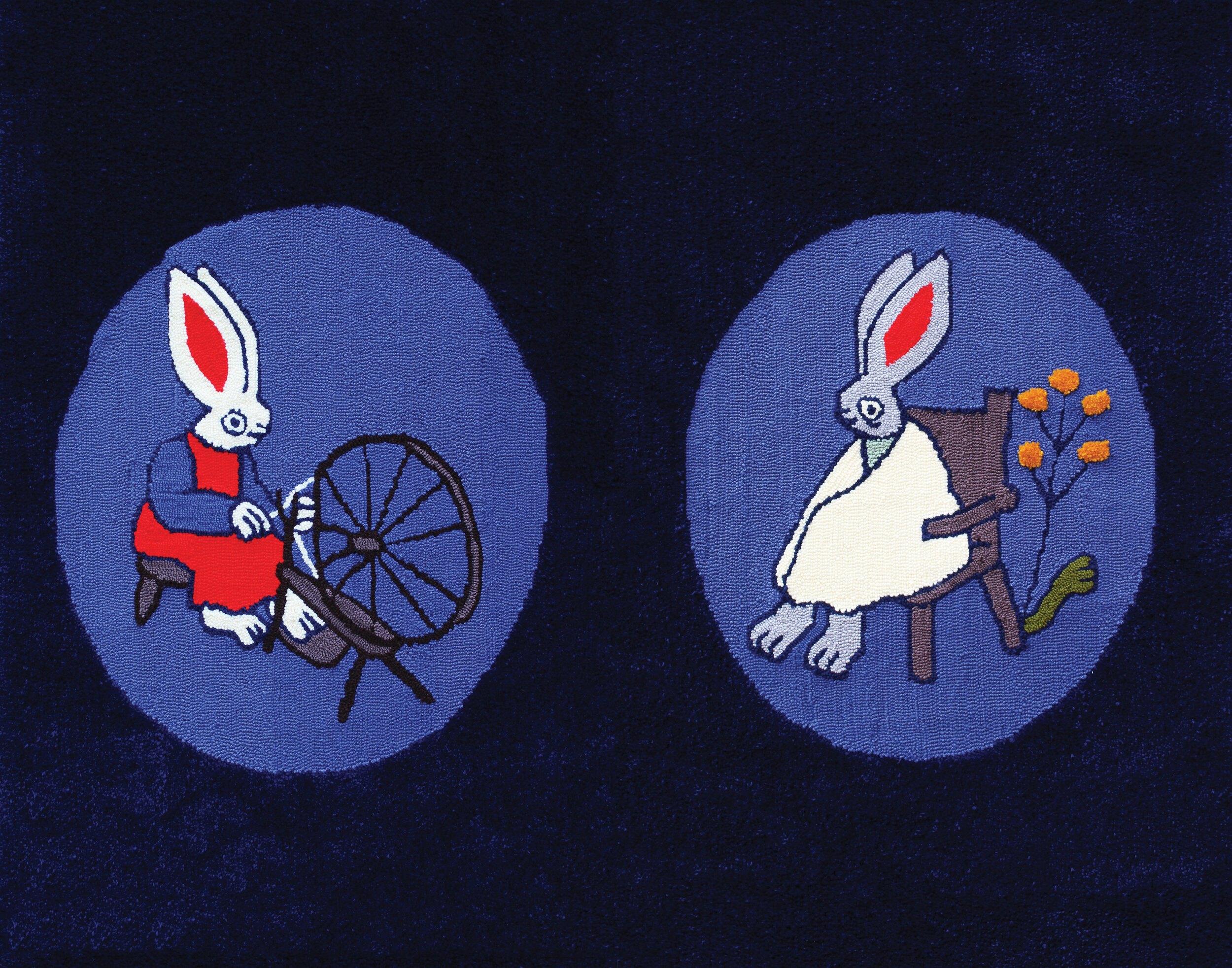

I became drawn to the medieval hare during my freshman year in college, after seeing their diabolical behavior in the marginalia of the Pontifical of Renaud de Bar. This liturgical illuminated manuscript from c. 1303-1316 contains legions of hares shooting crossbows and catapulting stones at knights, all in a lovely blue and orange color palette. I found the vacant expressions on the hares’ faces to be disturbing yet amusing. It was fascinating because the people of that era surely knew the horrors of war, and decided to turn them into an ironic vignette on vellum.

I loved the symbolism carried by hares- especially as seen in Robin Hardy’s 1973 film The Wicker Man. The hare may represent fertility, rebirth, and a turning of the tide- the hunter becoming the hunted. Wild hares can be quite unsettling, especially when compared to your common garden bunny rabbit. There is a genuine nothingness behind their eyes, yet they come out of the womb ready to run from a predator within minutes. Along with the nose twitching and gangly limbs, they fit perfectly into an early 70’s folk horror film. In The Wicker Man, a self-righteous police officer travels to a remote island in the outer Hebrides to search for a missing girl. He is repeatedly told by the island’s pagan inhabitants that the girl does not exist. Refusing to give up, he finds a grave marked with her name. The coffin is exhumed and inside it is nothing but the corpse of a spring hare, signalling the beginning of a new hunt.

I learned to knit during my first semester in Fibers, in Sam Field’s Sculptural Knitting class. We had an assignment to complete the sentence “knitting is ___.” I decided that if happiness is a warm puppy, then knitting is a warm bunny…

I made a miniature fair isle sweater, based off one Mathilde knitted in the 60’s that both my father and I wore as children. I was also very excited to learn cabling and made a little pair of green cable-knit trousers. I sewed a stuffed hare to wear the outfit, but it was too big for the trousers. Thus a second smaller hare was constructed, and a second outfit to match. Mathilde’s dementia was starting to get very serious and the two hares together reminded me of going on walks with her after school. Now they seem like a primordial form of Elisabet and the Ancestor.

Mathilde was always doing something with her hands- pottery, beading, crochet, and gardening. She tried to teach me to crochet when I was in preschool. After tightly braiding my hair and securing it with pink plastic clips, she demonstrated how to crochet a long chain. I couldn’t figure out how to recreate it. “If you lived in Puritan times, you wouldn’t be able to make your mittens and you would freeze to death,” she said earnestly. Perhaps this is why I’ve always preferred knitting.

Mathilde studied ceramics at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in the 1960’s, and went on to teach a pottery class at the Concord Academy. She recalled members of the Secret Service waiting in the hallway during class, as one of her students was Caroline Kennedy.

Her largest piece, a 20” goblet, took home first place in the 1976 Massachusetts Association for the Crafts exhibition. Her work carried itself with elegance and her skill was refined. She spent many hours in her basement studio and drove to craft fairs with “CONE 9” vanity plates.

Mathilde stated that she found inspiration in classical shapes and emphasized the relationship between form and decoration. She hoped that each finished porcelain piece would stand as a sensitive witness to the degree to which clay, glaze, fire, and herself were momentarily one.